Presentation of our guests

David Fauteux, Senior Innovation and Product Development Advisor at IDP

David Fauteux represents the Institute for Product Development (IDP) in this episode. He graduated with a Masters in Technology and Innovation Management and a Bachelors in Mechanical Engineering from Polytechnic of Montreal.

The main objective of the IDP is to make Quebec companies more competitive. It is a non-profit organization whose mission is to accelerate the adoption of best practices in product development and eco-design.

Carmen-G. Sanchez: Are there any steps that you would say are essential, really, in a process from ideation to commercialization?

David Fauteux: There are several. It really is from start to finish, and often that’s what you encounter and that’s what structures a product development process. The ones that are, not that they’re left out, but the ones that aren’t done all the time, or the ones that deserve to be done more at the start of the journey. It is precisely elements of strategic reflection of the product, positioning of the product. These are elements, when we talk about products, perhaps a little less technical, but which are the foundations of the product that will be developed. And understand the intention of the company and its products, as well as the product positioning compared to the existing one. Sometimes, we have a very good intention of a product that we want to bring. Finally, if we concretely analyze the market, is the market segment worth it? Are there already products that are a competition that are going to be hard to match? So this ability to process, to make certain macro portraits of the dynamics in which a startup wants to embark, is definitely crucial.

François Turgeon: Excuse me David, I would add something. I think that such an extremely important aspect for a startup, and for us, that’s what we did with Gaëtan for Constellation, is that we approached an incubator that really made a difference for us, because ‘we had a whole series of workshops that allowed us to reflect precisely and position our project.

David Fauteux: For us, in the product development process, there is a phase that is definitely more technical where we will get into the materials, in the construction of the product. This design phase is one phase among many others and at the end, the reasons why we work with companies to structure this product development there, with at the start, it is necessarily stages as we see; a little more market, a little more the state, the portrait of opportunities at a little more business level and later, it will give a little more technical. Then it will be the marketing, the commercialization. But this whole process, he is there to derisk the idea tomorrow morning. If I often follow this example, if we talk to Steve Jobs, probably there are a few people who, in terms of exceptions, do not need to structure themselves and who will be able to go there with the feeling that it will work. But for the majority, for 99% of the people that we are and in a business context where we are not necessarily the leader or the founder, we must be able to structure ourselves in order to be able to seek management of risk. Then it will be the management of technical, commercial and intellectual property risks. So you have to risk what it could in the end in order, as much for a startup, as an SME, as a large company, to maximize the chances of success in marketing the product. That starts from the beginning, from the idea.

Gaëtan Serrigny: I would like to second what David is saying, in the sense or in our startup experience, you have to be able to sell your product. You need to know exactly why you are doing what you are doing and how it will make a difference to get funding, to get partners. So this process, not only is it important for us, but the important thing so that we manage to create a network and that we manage to make people understand why we exist, why this project is important. And afterwards, of course, you have to find a structure, whether for the service chain, the production chain, and assess all the costs that will be undertaken in this phase of prototyping trials and therefore properly assess the resources needed to be able to knock on doors with very specific objectives, namely, to have confidence in why we do what we do.

Carmen-G. Sanchez: How do you tell a prototype from a minimum viable product?

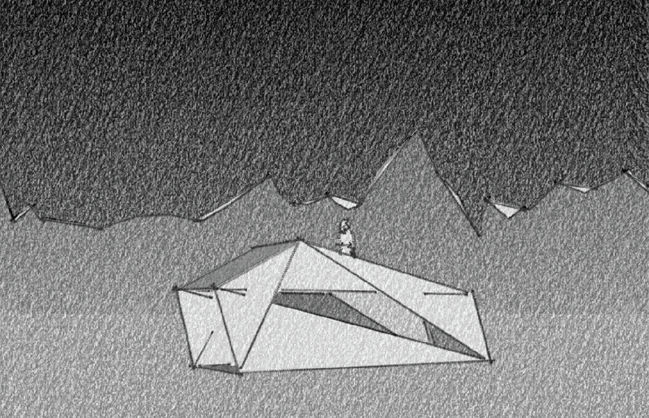

David Fauteux: Hmm, in my opinion, the minimum viable product, there is a commercial aspect behind what the prototype will not have. The prototype, which is there more for risk management, identifies from the first phases where the potential risks are, because a technology that we want to integrate is perhaps still in the infancy of its maturity, or because it there are elements that we are not sure we really know how to work. For example, the structure or the geometry, in the case of Constellation which could be evaluated. What geometry are we going to? So there are elements of risk, we were talking earlier in terms of risk management, so with regard to technical risks, we will identify them. The biggest ones, or those with the greatest potential impact in financial terms, if the technical risk materializes, or just if we are not able to achieve certain objectives, we will identify them and we will make prototypes. And that’s where we’re going to go, then we’re going to build a certain system in a simplified way. I take the example of Letenda, which is a startup that builds electric buses, but whose entire structure is made for electric motorization. And it is not a structure of a standard or gasoline bus that has been transformed for an electric bus, but everything is built from the start with respect to an electric motorization. Them very quickly, one of the prototypes they made was to build the interior out of cardboard, bring in different trades and ask them “Do you like that? “, because it is sufficiently different from what we could know in other types of buses. So sometimes, it’s a prototype that is not necessarily complex, expensive, but it allows to derisk a technical aspect. There may be some prototypes that are commercial. It can be small objects that we will make. Think of anything that can come out of a 3D printer under $1,000. Sometimes it will be to derisk, always with a view to risk management. And the prototypes have this function. Some are very minimalist. We’re going to talk about drawing, we’re going to talk about using cardboard to try to represent, but at least be able to draw conclusions. Then there are prototypes which can be very complex, which are practically the final product. But there again, it is in a prototype because we are going to do a series of tests with this prototype, to validate that things are working well. But the prototype, in my opinion, remains an element of risk management, versus the MVP, which is the first marketable product that will be sufficiently complete as a whole to go to market. Even if it may not represent half of the expected functions, there is enough to go and validate something, but not to validate it for free, it will still be validated in an offer on behalf of a company that will be able to benefit from it. So that’s kind of the distinction I make between prototypes and MVPs.

Carmen-G. Sanchez: Tell me, David, at what point do you have to worry about intellectual property in this whole process? Is this something that applies, for example in the case of Constellation or when developing a product? How it works?

David Fauteux: Intellectual property, depending on the market in which we are also, it is the maximum that you are able to put in lawyer fees to defend yourself if someone wants come and walk on your territory, if I may say so. For a startup, you have to ask yourself, how easy is it to copy our product? How costly is it if a player decides to come and take the same approach? I would maybe put a caveat sometimes, because especially for a startup, or when you deploy and move forward with a fairly innovative product, you are generally fighting against the status quo. So if another player comes in and develops something similar, or a bit different, is that really a competitor? I’m not saying if he wants to steal your patent, or if your patent is super important and there will be another person who will come and play a little on the same ground, but it will almost be an ally to beat you against the real competition which is the status quo. I take the classic example of an electric car. There are different players, but it can be done. The real competitor of the electric car is not the other electric car, it remains that it is the gas cars. So in his market, you also have to see, if there’s really just one player who can come back, is it worth it? In the notion of competition, or intellectual property, when we are in very innovative markets, I do not think it is the first factor. I am not saying that there is no consideration to be had. I think you have to ask the right questions, but I see it often and it’s often quite high costs. Is that the priority? It’s something to think about in my opinion.

Carmen-G. Sanchez: Is that something you consider on the Constellation side? Are there specific stages or products that you are thinking about intellectual property?

François Turgeon: Yes, in fact, it is certain, it is clear. And then I agree with your comment in relation to the fact that we are talking a bit about a piece of land, that we occupy a space, and then we still want to make sure of not having any bad surprises, that all of a sudden, someone picks up our idea and develops something similar. We thought about it, that’s for sure. I challenge anyone to try to do what we did. There’s a flap too, I think, at some point, it’s a bit like jumping into water. You have to have enough confidence that you will know how to swim too. And with regard to intellectual property, it is clear that one of the challenges for us is all the architectural plans. It means all the components of the product that make us really unique and that ultimately we are perhaps getting closer to a patent, or we are really getting closer to a very, very specific identity that cannot be copied. . And if it is copied, then we are effectively protected. I think that one of the qualities that we had with Gaëtan and with the various partners that we had, it is clear that the originality of the product, I think there is that too. For example, I make a reference to someone who invented a kind of one-wheeled skateboard and the idea, in fact, it is brilliant. It is very simple, it is like a skateboard, but the wheel is centered in the center. There is a motor which is integrated in the wheel and there you can move forward. Basically, we said to ourselves: yes, but I can, I can do the same thing, I can, I can copy, I can do it, but the engineering, the concept, the thinking behind it ensures that for someone who wanted to copy that idea, it would take a considerable effort. And it’s clear that we were thinking about that, we said to ourselves “Yeah, but if construction giants see our idea, and say to themselves, we could do the same thing. What would we do? “. Well me, at the same time, I tell myself if our idea is good and that people feel inspired, so much the better because I think it’s time to review the way we build things a little. I think it’s time we approach construction a little differently and find solutions. And if we can inspire these solutions to other producers or other designers, so much the better. But it is clear that Constellations positions itself, among other things, through its plans, through its various assembly and construction techniques to defend, of course, its intellectual property.

Carmen-G. Sanchez: How do you tell a prototype from a minimum viable product?

David Fauteux: Hmm, in my opinion, the minimum viable product, there is a commercial aspect behind what the prototype will not have. The prototype, which is there more for risk management, identifies from the first phases where the potential risks are, because a technology that we want to integrate is perhaps still in the infancy of its maturity, or because it there are elements that we are not sure we really know how to work. For example, the structure or the geometry, in the case of Constellation which could be evaluated. What geometry are we going to? So there are elements of risk, we were talking earlier in terms of risk management, so with regard to technical risks, we will identify them. The biggest ones, or those with the greatest potential impact in financial terms, if the technical risk materializes, or just if we are not able to achieve certain objectives, we will identify them and we will make prototypes. And that’s where we’re going to go, then we’re going to build a certain system in a simplified way. I take the example of Letenda, which is a startup that builds electric buses, but whose entire structure is made for electric motorization. And it is not a structure of a standard or gasoline bus that has been transformed for an electric bus, but everything is built from the start with respect to an electric motorization. Them very quickly, one of the prototypes they made was to build the interior out of cardboard, bring in different trades and ask them “Do you like that? “, because it is sufficiently different from what we could know in other types of buses. So sometimes, it’s a prototype that is not necessarily complex, expensive, but it allows to derisk a technical aspect. There may be some prototypes that are commercial. It can be small objects that we will make. Think of anything that can come out of a 3D printer under $1,000. Sometimes it will be to derisk, always with a view to risk management. And the prototypes have this function. Some are very minimalist. We’re going to talk about drawing, we’re going to talk about using cardboard to try to represent, but at least be able to draw conclusions. Then there are prototypes which can be very complex, which are practically the final product. But there again, it is in a prototype because we are going to do a series of tests with this prototype, to validate that things are working well. But the prototype, in my opinion, remains an element of risk management, versus the MVP, which is the first marketable product that will be sufficiently complete as a whole to go to market. Even if it may not represent half of the expected functions, there is enough to go and validate something, but not to validate it for free, it will still be validated in an offer on behalf of a company that will be able to benefit from it. So that’s kind of the distinction I make between prototypes and MVPs.

Carmen-G. Sanchez: How does it fit in with nature? I find it really magnificent and I think it opens the door to a next block that is more focused on eco-design, this kind of harmony, if you will, with different environmental factors. Maybe start with David, how do you interpret eco-design versus traditional product design?

David Fauteux: We interpret it quite broadly. Basically, if we go back to eco-design, it is to ensure that the product has the least possible impact on the environment. And as we see, the product, yes there are the slightly more material elements and the energy, but in the end, we see that the product and its business model, and its stakeholders, and the challenge , so it’s much wider. This is why we talk about it more at the Product Development Institute as being sustainable innovation, because it is also a driver of innovation. These are constraints that we give ourselves, that we bring to ensure that our environmental impact is not high. As much as we could have financial constraints, we have technical constraints when we develop a product and by giving ourselves environmental constraints, inevitably that will help us to innovate, and to innovate in a different way, because the model will have to be different, because that we can no longer afford to have such and such a rejection, or such an impact in relation to our product. So, when we talk about eco-design, there is the notion of the product which is central, which will come down to an impact on the functions, on the characteristics of the product, but the reflection is much broader and starts from a idea too; the company has to want to change, it has to want to change for the good of certain issues.

Carmen-G. Sanchez: How did you manage to minimize the environmental impacts of your project?

Gaëtan Serrigny: I think that first of all, it is a choice of materials. So sometimes, if we go for the simplest, that’s not where we’re going to find them. On the other hand, if we carry out a slightly more advanced research process — wood is already a renewable material, and in addition it can have local suppliers — we can have ecological cuts that respect a certain cycle of the forest, and therefore I think it’s a desire for research. Basically, it is also a desire to create this circular economy which is something that is increasingly being put into practice in Quebec, which is great. The rest of one’s production process can become the beginning of another’s production. And so, I think what is great about eco-design is that it is precisely a value that yes, it requires more research. Yes, sometimes there is a cost associated with that, but it is a value that is increasingly taken into account by the market and by the user experience. So we said to ourselves that if we want to have an experience in nature as much as it is done in an environment that is completely thought out with the protection of it.

François Turgeon: Yes. Then, I would add that eco-design is at our heart, in fact we were quite lucky because our first customer is located five kilometers from the shop where our ecopods are produced. So, in terms of GHGs and transportation, we were extremely lucky, because if we had had our first prototype sent to the Gaspé, there we might have had a slightly more negative impact in terms of GHGs. I’m thinking of one of the things I heard lately that really had a big impact on me as an entrepreneur, it’s a guy called Gary V. Is that it, Gaëtan?

Gaëtan Serrigny: Yes, it’s Gary V.

François Turgeon: So it was through Gaëtan, I think, that I discovered this man, but anyway, he said something on Instagram that I really liked, he says, “ Kindness is a super power ”. And I found that very beautiful, because I think that — and that’s what I was saying at the start — for a company, the ultimate goal is not to make money. The ultimate goal is to meet a need. Yes, you have to make money, but especially in entrepreneurship and especially at the beginning, the problem — then I know, I had this experience — is to underestimate the needs. And if we underestimate our needs as an entrepreneur, we find ourselves in a situation where there may be financial problems; we did not plan for certain costs, we did not plan to set up our prototypes, etc. was going to ask us for more resources… I think that eco-design somewhere is also this desire to say to ourselves, here we are, we are perhaps not at present — if we evaluate our eco-design at present, we are perhaps at 20%, 25% or 30% of what we want to be. Ecodesign is very complex, it affects a lot of parameters and one of the things we did with GAE is that we set up a project with ÉcoLeader which must help the company to position it, but also to develop more defined processes in ecodesign. I’ll give you a very, very simple example. Ecodesign can, for example, be offered to an entrepreneur: I have employees who have to travel 40-50 minutes away from my offices. The employer can decide, for example, to rent houses or allow its employees to have a space to stay during the week to reduce greenhouse gases. Ecodesign is also, I think, a huge way to change the lifestyle of employees. Me, I saw it and we work with our production sector with an extraordinary man called Robert Rondeau who came to the aid of the project. Robert, it’s been 25 years under construction. He’s made his own boat at some point, and Robert certainly has extraordinary quality, but he has a certain classic builder’s instinct. And it is precisely this aspect that we develop with him, to ask ourselves how we can improve production? What we would normally throw in construction, we want to revitalize it, and it is this kind of change, this pivot of thought, which means that in the end, eco-responsibility can become a superpower. And the people who are going to buy our structures, they are going to buy them thinking that maybe per square foot it’s more expensive than a normal house, but I know that with the structure and the effort that was done, I understand and I see the validation of the different stages of production, and I think it’s a good investment. At that time, the costs and responsibilities